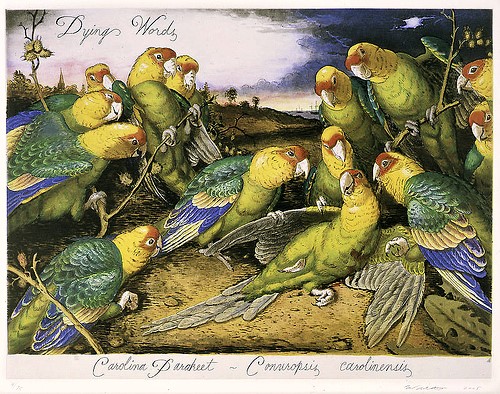

Once there were parrots in this forest. Maybe the oldest trees remember them, since it wasn’t that long ago. The reasons they’re gone are tangled and various – even the details of their biology weren’t well understood before they vanished.

As a schoolchild I learned about Martha the Passenger Pigeon, the last of billions, who lived out her long life in the Cincinnati Zoo (she never lived in the wild). I was a sensitive child, and mostly empathized with her loneliness – the hugeness of species extinction was beyond my mental grasp, and in some ways still is.

But nobody mentioned the Carolina Parakeet. Which is odd, since the beauty alone of this bright parrot would make it an especially poignant icon of extinction. The last one collected from the wild (outside of Florida) was in Kentucky in 1878. The Florida birds survived into the early 20th century; possibly finished off by poultry disease, as they were tame enough to forage on the ground near barnyards.

Audubon’s incredibly lively painting (achieved by wiring up specimens in lifelike positions) captures the true character of these birds – noisy, social, smart, curious. And, no surprise – destructive to crops and orchards. Hated by farmers, they were also shot by sportsmen, feather collectors, museum collectors. It was surprisingly easy to kill dozens at a time, since the cries of a wounded bird brought the whole flock back to its side.

To digress a bit, on the topic of museum collecting – 19th century ornithology was mostly practiced through a gunsight, since “opera glasses” (as binoculars were called) had very poor optics. The only way to get a good look at a bird, or any other animal for that matter, was to shoot it. By century’s end the zeitgeist, thankfully, was turning away from such destructive practices, pushed on by younger ornithologists like Frank Michler Chapman. Though a dedicated collector, he was obviously miserably conflicted. In this excerpt from an 1890 letter to his older colleague William Brewster, Chapman expresses his self-loathing:

This miserable collecting. It is the cause of all higher failing, it lowers a true love of nature through a desire for gain. I don’t mean a specimen here and there, but this shooting right and left, this boasting of how many skins have been made in a day or season. We are becoming pot-hunters. We proclaim how little we know of the habits of birds and then kill them at sight. Sometimes I am completely disgusted with our ways and myself in particular… I long for an outing where the gun will be secondary, recorded observations primary, where I shall be entirely alone or with a companion whose object is my object.

We have Chapman to thank for the original idea of the Audubon Christmas Bird Count, a much-loved birding tradition that began as a way to promote watching birds, not killing them.

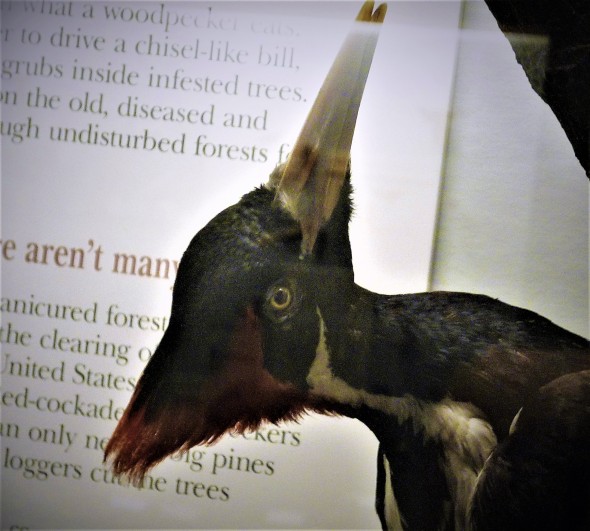

Of course “skin” collecting is why the Field Museum in Chicago has so many specimens in its drawers. We visited just before Christmas, and my family, frustratingly, didn’t want to linger in the amazing bird displays. I did manage to snap some pics of the extinct birds, since I can’t see them anywhere else(!) and just had to write a blog post about it.

But back to the parrot. Carolina Parakeets were a Pliocene relic, along with such plant species as Passionflower and Pawpaw trees. All have numerous relatives in the tropics – but only one species that managed to tough it out in the temperate zone when the climate cooled. (Interestingly, the mid-Pliocene is considered a possible model of future climate, as it was somewhat warmer than now).

By coincidence, I made friends recently with one of the Carolina parakeet’s closest living relatives, the Jenday Conure. (Another close relative, the Sun Conure, is endangered and dwindling fast, thanks to the illicit pet trade.) The Jenday was living at Sandy’s pet store, where the birds are allowed to perch on you if they want to. Playful, smart, loud, with a very strong and busy beak – I can only imagine what havoc a large flock of such parrots could create. And Carolina Parakeets might get their chance again, thanks to…

DE-EXTINCTION

It’s not science fiction anymore, and though the Carolina parakeet is not currently on the to-be-revived list, it likely will be one of these days. (Parrot breeders are trying to create a look-alike; not the same genetically.) The Passenger Pigeon and the Heath Hen are the first candidates for avian resurrection in North America.

To understand the de-extinction concept, we need to think of a species less as a fixed entity, and more as part of a mutable continuum of related species that share portions of their genome. Rather than cooking up an extinct species from scratch, scientists would do genetic cut and paste on embryos of its closest living relative. Obviously, good candidates for de-extinction need to have close living relatives. Though I won’t dwell on the science, these links lay it out in a most interesting way.

http://reviverestore.org/projects/the-great-passenger-pigeon-comeback/

http://www.audubon.org/news/what-would-happen-if-we-brought-birds-back-dead

However you feel about gene meddling, and whether we should or shouldn’t, it’s a good bet that some extinct species will be resurrected. Though a cynic might think the reason is “because we can”, the scientists working on such projects are careful to insist otherwise. The extinct animals chosen will hopefully step into their former role of ecosystem engineers, and assist in reviving their historic habitats. In the case of the Woolly Mammoth, a good portion of it’s historic range has been little altered and is mostly unpeopled.

Not so with the Passenger Pigeon and Carolina Parakeet, whose former ranges encompass the now bustling Midwest/Eastern US. The Carolina Parakeet was destroyed, in part, because it was considered a threat to agriculture – boisterous flocks converged on grain sheaves and orchards. Both species thrived in huge flocks, suggesting they may need to be incredibly fecund to be successful. Worst case scenario – we could end up inflicting another Starling-like nuisance on ourselves and native species.

“Species can either fail to thrive or thrive too well, or in a way that humans don’t like,” says George Church, a geneticist at Harvard University. “If you bring back one species that causes the demise of another, you get a zero sum or even negative sum game.”

As much as I would personally like to see Carolina Parakeets back in their native habitat, I can imagine that Woodpeckers and Wood Ducks might not agree. The Carolina Parakeet was also was a cavity nester, and its presence would undoubtedly affect the number of tree holes available to other species. All creatures exist inside an infinitely complex web of complementary dependencies. Even ones that used to belong here, could prove disruptive to an ecosystem that has long since moved on without them.

Though I sound like a naysayer in regard to de extinction, it’s only because I’m more concerned about birds that aren’t extinct yet, but just fading away. In my lifetime I’ve witnessed the decline of once common birds such as the Wood Thrush, Bobwhite, Red-headed Woodpecker, Field Sparrow, Whip Poor Will, Nighthawk….. and there isn’t any single reason for their gradual slide, though the usual suspects are surely involved.

As exciting as it would be to have Passenger Pigeons, Carolina Parakeets, Auks or Mastodons back from the dead – I’d be happier just knowing the fluting song of the Wood Thrush won’t fade away.

sweetgumandpines

I recently saw a couple of stuffed Carolina parakeets at the National Museum of Natural History in DC. A poignant sight. I would dearly love to have wild parakeets in our woods,

Given their tendency to go feral and survive outside their natural range, I wonder if monk parakeets will one day fill the niche left vacant by Carolina parakeets. The monks aren’t cavity nesters, but that might be an advantage in the suburbs.

LikeLike

oneforestfragment

The Monk’s communal nests and broad eating habits are certainly the key to their success. Cavity nesters are always limited by the # of available holes in trees, since only woodpeckers can make them. Really wish I’d known about the Chicago population before our trip, would have liked to see them. It’s illegal to sell them in KY and a # of other states.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jim Sky

I have not thought much about ecological impact of bringing back a bird species. Thanks for your well spoken perspective. The same I think could be said for an insect species or any type of animal that could not be easily controlled if released.

I don’t think the same would apply to the woolly mammoth. The objection I hear about engineering a mammoth is that it would be cruel. Really? I hate to use the “what about X” rebuttal but it fits well here as we condone feedlot meat and zillion other injustices on our neighbors. I can quench my guilt enough that I still want to see the mammoth as our ancestors did, (only be a lot nicer to it than they were).

LikeLike

oneforestfragment

Thanks for the comment Jim,

It does seem the Mammoth would be a safer choice. An Asian Elephant, as closest relative, would bear the first embyros. It’s also quite odd to think of reintroducing an extinct elephant when another species of same is dwindling so rapidly. Would it also be killed for it’s ivory?

LikeLike

Jim Sky

People are recovering and selling mammoth ivory. It is legal.

https://www.boonetrading.com/collections/mammoth-ivory-bone

It feels creepy to me. It may even make the trade in elephant ivory worse.

https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/08/wildlife-woolly-mammoth-ivory-trade-legal-china-african-elephant-poaching/

So maybe it is a bad idea to bring back something we would abuse. I didn’t even think about the ivory.

LikeLike

oneforestfragment

Good point Jim – In regard to de-extinction, how would laws that pertain to living animals and endangered species apply to ones that are/were extinct?

LikeLike

Anonymous

I did’t know we ever had wild parakeets in Kentucky. You continue to be a fascinating educator.

LikeLike

oneforestfragment

Thank-you, I just have on overly busy mind sometimes. And it’s fun.

LikeLike

Michael Smith

Let me see if I can do better this time. I did’t know we ever had wild parakeets in Kentucky. You continue to be a fascinating educator.

LikeLike

oneforestfragment

Thanks Mike! I will keep on sharing fascinating things from our little forest.

LikeLike

kennytikals

Just heard a NPR report on a graduate student who is taking a new look at the Passenger Pigeon, and all the factors that contributed to its demise, and as a candidate for “revival”. Forgot the name of its closest pigeon ancestor today

LikeLike

oneforestfragment

It’s closest to the Band-tailed Pigeon of

LikeLike

oneforestfragment

It’s closest relative is the Band-tailed pigeon,so a revived Passeneger Pigeon would be a hybrid with dna of both.

LikeLike

Brad Feger

I heard on NPR that there is a population of parrots in Brooklyn, NY, thought to number in the hundreds, that live almost exclusively on the campus of Brooklyn University. They were brought to JFK airport Argentina in 1978 and escaped when authorities became suspicious of their container, thinking that a large (and probably noisy) crate from South America might be linked to the NY Mafia. Upon opening the crate, the parrots flew out and bewildered the authorities, who obviously failed to catch them. A man named Stephen Baldwin (unrelated to the actor) gives tours on campus of the odd New York parrot population, and he said that they’re thriving due to New York being a similar distance from the equator in the Northern hemisphere as Argentina, thus having a similar climate. They’ve adapted by having a fortunately-undisturbed habitat on the campus and varying their diet to things like the local tree seeds and fruits and yes, even garbage. They’ve been seen, much like other New York scavengers, to fly away with discarded slices of pizza! I don’t know that they’re considered a nuisance by people there and it seems they’re quite admired. I think it’s interesting and pertinent to this post, and perhaps shows that yes, the Carolina parrot could very well thrive if “brought back to life”, although it’s impacts to our current ecosystem and popularity among humans are still unknown. Very interesting post!

LikeLike

oneforestfragment

Thanks Brad,

You are right – around the world escaped “pet” parrots are adjusting to city environments. Another interesting aspect of the Anthropocene – cities may well become better habitat for some species than the habitats they evolved in. Many parrot species are dwindling quickly in their native landscapes due to deforestation, the pet trade etc. I learned a lot from this website

http://cityparrots.org/

They advocate for feral parrot populations in cities.

LikeLike

Anonymous

You may find this links interesting:

http://rule-303.blogspot.com/2013/07/while-working-on-my-newest-article-for.html

LikeLike

oneforestfragment

Very interesting, thanks! There is certainly evidence in the genetic record that the extremely large populations seen in the 1800’s were not sustainable, and may have been due, in part, to anthropogenic changes.

LikeLike

Courtney Ellis

I really enjoyed this! Wonderful! I can’t believe how fascinating this topic is! Thank you for writing and posting this!

LikeLike

oneforestfragment

Thanks Courtney! It was fascinating to research this post too, I learned a lot.

Thanks Courtney, I enjoyed

LikeLike

Pingback: 5/17 Birdy – one forest fragment