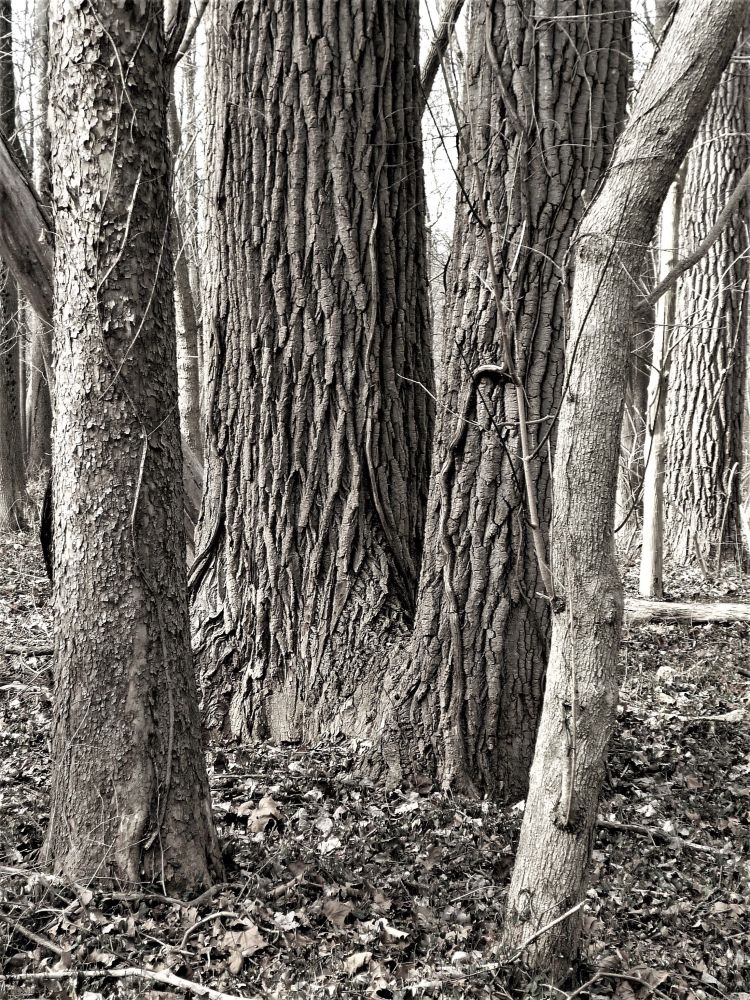

Trees, like people, need to dodge a lot of bullets to get really old. The shade of other trees, browsing animals, insects, disease, wind storms, buck rubs, people with chain saws, and just plain bad luck. So many ways to lose out, it’s amazing that any tree makes it past 100 years. Even more so in this little fragment of forest, that has endured a succession of anthropogenic impacts over the last 200 years. There are just a few older trees left here; these survivors have been witness to the gradual fading of a remarkable landscape.

Call me a romantic, but reading about the natural history of eastern North America makes me want to go back in time. Maybe just for a little while; I’m not usually someone who glorifies the past. What I’m longing to see is Carolina parakeets, Ivory-billed Woodpeckers, trees that dwarf me, the songs of neotropical migrants ringing out through the forest. They were here when this preserve was just a tiny part of the great expanse of forest that cloaked much of the eastern US. Now in this forest most of the spring ephemeral wildflowers are gone, and the witchhazel, the blackhaw, the ginseng, the orchids. Frogs and toads, gone. Most of the surviving native flora hangs on under increasing deer pressure. But some old trees remain, though fewer every year.

It’s hard to enough take pictures of big trees in a way that expresses their size. But there’s no way to capture the sense of awe I feel in the presence of these survivors. Standing at the base of the Hackberry, Celtis occidentalis, in the above image, I can see into the hollowing heartwood through an old healed wound. I have to tip my head way back to see the upper reaches of massive limbs, each one as large as a good sized tree.

Why did this one survive so long? I’ve seen many younger Hackberries crash down, and they didn’t have a gaping hole in their trunk.

Large doesn’t always mean old. Younger trees in very favorable situations can get big really fast, and most trees reach maximum height in their first 100 years. But the Black Walnut, Juglans nigra, (in the opening pic and above) seems to have some true characteristics of age, such as deeply furrowed bark and massive limbs. I measured its circumference – 145 inches, then used a formula developed by the International Society of Arboriculture to estimate its age. Dividing 145 by 3.14 (pi) gives a diameter of 46.17 inches. Multiplying by the “growth factor” for Black walnut, (4.5) gives an age approximation of 207 years. This is in no way a really accurate method, but the estimate is close to what I would have guessed. The massive side limb tells us this tree had plenty of room to spread out when it was young, and likely stood in an open pasture.

In contrast, this giant Pin oak, Quercus palustris, has most of its huge limbs clustered near the top. Though it’s a big tree, it may not be especially old since Pin oaks have a fast growth rate. In my neighborhood Pin oaks were planted along the sidewalks about 70 years ago when the houses were new. They’re quite huge now, and and many are succumbing to the various issues urban trees are subject to.

An interesting piece on how to recognize older trees:

Click to access CharacteristicsOldTreesNAJ_2010pederson.pdf

The pic below is the mossy base of the largest Tulip tree, Liriodendron tulipifera, I’ve seen in the preserve. It’s old enough to have chunky bark very unlike a younger Tulip tree, and it’s very presence is surprising; straight grained Tulip trees like this one are valuable for timber. That’s likely why there are only a handful of mature Tulip trees left in this forest.

Tulip trees are fast growing – this one has a diameter at breast height, or “DBH”, of 40.4 inches; multiplying by the species growth factor of 3 yields an age estimate of only 120 years.

But Shagbark Hickories grow much more slowly. The one above can be seen beside the old Prather road near trail post #10. It’s not especially big, but has characteristics that suggest it’s fairly old, such as “balding” of sections of bark and twisting of the main trunk.

With a circumference of 118 inches and a DBH of 37.5, this Shagbark isn’t unusually large. But the growth factor is 7.5, so the age estimate for this tree is 281 years. I doubt it’s quite that old, since it’s on a bottomland site with rich moist soils.

A few hundred feet further along Prather road stands this truly big White Ash, Fraxinus americana, an old survivor that recently succumbed to infestation by the Emerald ash borer. (see my post of 2/25/17 “Goodbye, Again”). Though it certainly looks old, I’m basing its age estimate on a DBH of 57, when multiplied by the White ash growth factor of 5 = 285 years. Though again this is likely an over-estimate, what’s left of this tree is impressive.

Its lower bark has that uniquely distorted pattern common to older trees.

Smaller limbs are now falling off this decaying hulk, encrusted with a variety of lichens which can also be quite long-lived.

Although it involves a lot of uncomfortable neck bending, I enjoy studying the upper canopies of large trees. Their limb development is uniquely influenced by the presence or absence of nearby competitors for sunlight. These two Sycamores, Platanus occidentalis, have grown up together, and formed large side limbs that branch away from each other.

The old Shagbark hickory by Prather road must have lost the top of its canopy long ago, with the remainder of the tree seriously skewed off sideways. Hickory wood is known for its incredible toughness and bending strength, so perhaps being bent over this way is not a problem for the tree.

I did not try to estimate the age of this triple trunked Sycamore, since its diameter is obviously much greater than other Sycamores of the same age, and would have resulted in a very inaccurate estimate. This hidden treasure of the preserve isn’t near any trail, but I’ve taken a few friends to see it.

The three foreground trees above are, L to R, Sycamore, Cottonwood, Boxelder. They’re growing very close together, and the small Box Elder is leaning outward to the light. Box elders are fast growing, shade tolerant and relatively short-lived maples. But the young Sycamore tree’s future depends on the eventual decline of the Cottonwood, so that it can come into its own as another forest giant. These relationships can be observed in most forests if you take the time to observe trees.

Sadly, the trees most lacking here are young saplings. They should be more abundant, especially in light filled gaps and beneath the many dead Ash trees. Although Box elder is regenerating well, it’s especially hard to find young Sycamores, Tulip trees, Hickories or Oaks. Decades of deep shade from invasive Bush Honeysuckle suppressed most native plant species including young trees. Now that we’ve made great progress with invasives removal, there’s a new threat: increasing numbers of deer who love to browse young trees. It’s a hard life for little trees in this forest! To ensure there will be big old trees here hundreds of years from now, we’ll have to plant the future forest giants – and put a sturdy deer proof cage around each one!

Elizabeth

Excellent post as usual. I remember that impressive triple trunk sycamore.

Love the heart shaped tree scar at the end, for Valentin’s Day!

LikeLike

oneforestfragment

Thanks Elizabeth! I just happened to finish the post today, so got to use that pic.

LikeLike