Say Goodbye, Again feb.25

One more tree species bites the dust…

a longer post than usual.

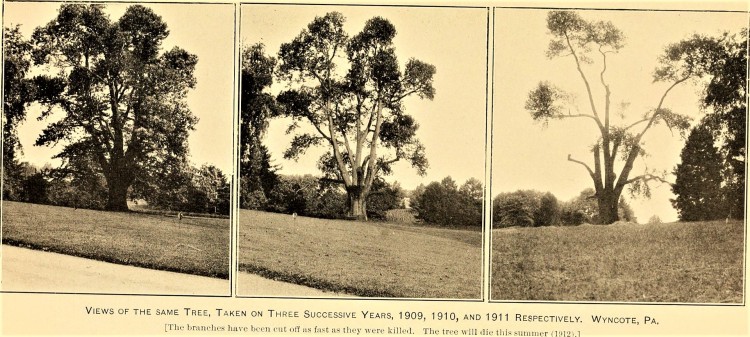

How can a tiny bacteria, fungus or insect wipe out a whole species in a short amount of time? The most destructive forest insect to ever invade the U.S. is in our forest now, and most of the ash trees are dying or already dead. Painful as it is to see, there is nothing we can do. This isn’t the first time an exotic organism surged through our forests and took out a keystone tree species. To better understand why this happens, lets look at some of the earlier tragedies.

Once upon a time, the American chestnut was a mainstay of eastern forests, reaching great height and girth. In the early years of the 20th century we learned the true price of global trade, when the pathogenic fungus Cryphonectria parasitica got off the boat from Japan in a wood shipment. It proceeded to kill almost every American chestnut, a species of great economic and wildlife value (there were as many as four billion trees). Cankers erupted from the bark of infected trees and quickly resulted in death due to chestnut blight disease.

Chestnuts growing in isolated locales were spared from the wave, and they became the starting point for recovering the species through breeding with resistant asian chestnuts. Current research focuses on genetic modification, by adding a gene from wheat that protects against the fungus. It’s a complex process that’s taken over ninety years, but healthy resistant trees are now being grown.

- resistant 15/16th American chestnut at the LNC- there are three, planted and tended by the American Chestnut Foundation

Time for some science – what exactly does “resistant” mean? For a species to develop resistance to a pathogen, a huge number of non-resistant individuals have to die. This leaves the lucky few with resistant genetics to repopulate. In the case of the Chestnut blight, we can assume the fungus causing it has preyed upon chestnut trees in Asia for a very long time, long enough for resistance to develop (the chestnut genus Castanea is at least 65 million years old, and likely originated in Asia). That’s why scientists turned to the genetics of asian chestnuts to “fast forward” the work of restoring the American chestnut – they fought that battle long ago and survived.

- What’s left of an American elm, near post #19 in our forest

In our forest the next major wave was Dutch elm disease, which occurred in my lifetime. I can still remember the grand old American elm that landed on my father’s car when I was a teen. The pathogen in this disease is also a fungus (Ophiostoma nova-ulmi), but it is harbored and spread by bark beetles, both native and exotic.

The skeletons of these elms still rear up here and there in our forest, and their large limbs continue to fall off, adding to the abundant supply of downed wood. The species is not all gone. Thanks to resistance shown by cultivars, which over time will cross with typical natives, we may see a recovery of the American elm.

But the worst is still to come.

Because this innocent looking little hole….

means the death of this huge ash tree, and hundreds more like it in our forest. And who knows how many millions, eventually billions in the whole eastern US. You’ve heard of it by now – EAB, short for Emerald ash borer. Unlike many of the other tree plagues, there are no fungi involved here. The larva of the beautiful iridescent beetle Agrilus planipennus does the damage all by itself.

EAB infestation was first noticed in Michigan in 2002, some time after larvae had arrived from Asia in a wood shipment. (If you’ve noticed the Asia connection for invasive pathogens, there is a reason. Pangaea, Big ice, and north -south mountain ranges explain most of it. Our Midwest flora has much more in common with China than the western U.S. A story to explore in a future post)

EAB larvae tunnel and feed throughout the living cambial layer, starting high in the trees and moving lower each year. So infestations are often not noticed until the tree is nearly dead. It only takes a few years to kill a tree when ash borers reach peak abundance in a forest.

Our forest, which is rich in ash trees of all sizes, is likely near that stage now. Older ash trees are particularly abundant on the floodplain – depending on the site, ash species comprise 40% to 80% of the midsize and larger trees.

- White and Green ash have a distinctive bark pattern that’s easy to spot

But there may be a silver lining, if you can call it that. Over the last 50 years our forest trees have continued to close the canopy, with less light going to the understory. Sadly, an invasive shrub invasion was underway too, with shade tolerant species like privet and honeysuckle coming into dominance. Now the opposite is occuring – invasive species removal plus EAB death equals a lot more light. The site of just one old ash tree’s demise can be considered a forest “gap”, the place where regeneration takes place. Some ash trees are already dismembering, as in the photo below, where one half the tree slabbed off in high winds.

So is this an opportunity or a nightmare? That depends on our actions as forest managers over the next few decades. All this sunlight pouring in could help revive an understory community of young trees, and gap colonizers like Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) and Spicebush ( Lindera benzoin). Or the invasives could all grow back with renewed vigor. Likely it will be both scenarios, with increased growth rates of native and invasive plants, and continual vigilance needed to keep the revival on track.

- Pawpaw fruits in our forest

But something good is trying to happen – Spicebush regeneration from seed, documented by all those little red flags – is occurring at a surprising rate in some places. Scores of tiny ones may surround a large Spicebush that is a copious seed producer.

- Spicebush berries in October

Very young spicebush are so abundant in spots that we’ll be transplanting some to a nursery site near the LNC, to “grow out” in sunlight and great soil. These plants will return to the forest when 2 to 3 feet tall, to areas where no spicebush currently grows.

Though Spicebush is adapted to grow in understory shade, with increased light it produces berries much more abundantly. Only female plants grow them, but an eight foot or taller bush can make hundreds of deep red berries. So the increase in light levels will speed up a Spicebush revival. And this is a great plant to have more of – unbrowsed by deer, it’s one of the most common shrubs of moist eastern forests. The lipid-rich berries are fuel for migrating thrushes, in particular.

Of course we cannot really understand all the complex interactions that will be altered by the loss of our ash trees.

Though there are few positives with such a huge forest die-off, in our particular case it may be a chance to revive an understory community that was overwhelmed by invasive plants. It’s good to remember that in nature, change means opportunity. And for woodpeckers at least, it’s a real windfall.